“Most people see their life flash before their eyes when they’re dying,” Harley Flanagan tells me. “I’ve been watching mine on a movie screen, night after night, in front of strangers.”

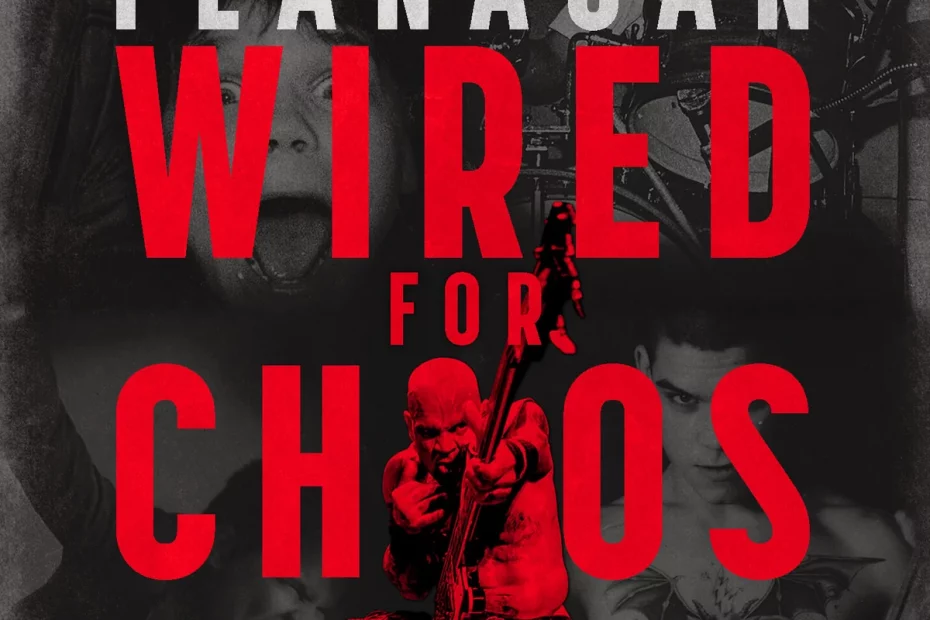

The film in question, Wired for Chaos, doesn’t follow the usual rock doc template. Sure, there are some neatly edited montages of stage dives and a who’s-who of talking heads with elite punk and hardcore credentials. But it goes deeper. A psychic excavation: raw home footage, bursts of archival chaos, and long, still frames of a man sitting with his past—and deciding what to do with it. Scored with the raw tension of underground punk and assembled with near-impressionistic pacing by Rex Miller, the film feels less like a documentary and more like a séance with the past.

The film’s emotional weight lingered long after the credits into an exclusive interview over coffee the following morning as Seattle warmed into a summer heat bubble. Over the course of our 90-minute conversation, we covered the expected terrain—New York’s hardcore scene, Cro-Mags, violence, family, recovery. But what stuck with me isn’t the mythology. It’s the humanity. The unvarnished honesty of a man who has every reason to be guarded, but chooses, repeatedly, to be open.

“I realized I don’t feel normal unless I’m in a state of fight-or-flight,” he says early on. “That’s not some metaphor. That’s just my nervous system.” When he said it, his shoulders relaxed just slightly, like releasing the pressure of truth before it built too far. He wasn’t posturing. He was confessing. To me, and maybe to himself.

The Warrior’s Wiring

Born into the chaos of downtown Manhattan in the 1960s, Harley’s childhood reads like a punk dystopia crossed with a beat poet fever dream. His mother, Rosebud, was a free-spirited artist connected to Warhol’s Factory and the Lower East Side counterculture. But the bohemian glamour masked a daily reality of instability, addiction, and danger.

“I was the baby on the dirty mattress while the adults were freaking out,” he says. “Somebody was OD’ing. Somebody was getting fucked. Somebody was getting beaten. That was just normal.” He knew what sex was before he knew the alphabet. Hitchhiked across Europe with his mom; clawed at a trucker as he tried to rape her and played music for spare change on the street before most kids learned long division. “I didn’t have a childhood,” Harley tells me. “I was in rooms full of grown-up depravity from day one. I was wired for chaos before I even knew what chaos was.”

By the time he was ten, he was playing clubs. At thirteen, he dropped acid with Adam Yauch and saw A Clockwork Orange. At fifteen, he was immersed in the tribal warfare of New York punk’s early years, gravitating toward skinhead culture—not for fashion, but for survival. “To me, being a skinhead was about not taking any shit,” he says. “It wasn’t about style. It was about not getting stomped.” And yet, despite the layers of armor—literal and emotional—Harley, at the time, was crumbling inside.

Rage as a Regulator

“I didn’t even realize I was a ‘Rageaholic’ until this last year,” Harley says, laughing without a trace of irony. “I was 58 years old, walking through the park, cursing out loud, getting myself wound up. And suddenly I stopped and thought: Who the fuck am I yelling at?” The realization hit like a brick: rage had become his nicotine. A necessary hit to feel anything close to normal. “When you grow up like I did, you’re in fight-or-flight mode 24/7,” he says. “That becomes your homeostasis. That’s your baseline. I didn’t know how to function without it.”

He’s learning now, through therapy and connection. His combat vet friend, Jocko Willink, was the first to name it: PTSD. The rage, once a shield, became a prison. And when it no longer served him, it nearly killed him. “It’s like waking up every day and your brain is scanning for war,” he says. “Except the war’s over, and you’re still armed to the teeth.”

The Strength to Speak

One of the most thought-provoking moments of our conversation came when Harley reflects on trauma—not with shame, but with clarity. “You’re not vulnerable when you talk about it,” he says about the film. “You’re vulnerable when you can’t. When it’s bottled up inside you, that’s when it eats you alive.”

That sentiment echoed through our conversation, especially when we talked about sexual abuse. Harley speaks frankly about being molested as a child—often by older women, but also, one time in particular, by a man who drugged him. He recalls the moment with visceral detail. The disgust. The paralysis. The rage that followed. “I buried that shit so deep,” he says. “But it didn’t stay buried. It came out in violence. In addiction. In the way I treated myself and others.”

For years, it was an afterthought, out of mind; it was just “life.” But therapy helped him reframe it. “It’s not weak to admit you’ve been hurt,” he says. “It’s weak to lie to yourself about it.”

Parenting as Reclamation

If there’s one place where Harley’s tone shifts, it’s when he talks about his sons. “For a long time, I was reliving my childhood through them,” he says. “Taking them places. Doing things with them I never got to do. I was being the parent I never had.” When he lost access to them, after Webster Hall, during family court proceedings, it nearly broke him. “It felt like I was losing my own childhood all over again,” he says. “Like someone ripped out the only part of me that still felt innocent.”

But that story, like so many others in Harley’s life, didn’t end there. He fought. He stayed present. And now, years later, he talks to his sons almost every day. “They love my wife,” he says, smiling. “They talk to her about shit they don’t even talk to me about.”

The Film and the Fallout

Wired for Chaos premiered to sold-out crowds and stunned silence. The film’s rawness—the jagged footage, the brutal honesty, the refusal to resolve—left audiences shaken. Many stayed behind for the Q&As, some to praise Harley, but an equal number to unburden themselves.

“I’ve had vets tear up and tell me about all the friends they lost in combat after screenings,” he tells me. “People with cancer. People who were abused. They tell me my music helped them survive.” The catharsis cuts both ways. “It’s beautiful,” he says. “But it’s heavy. Every screening is like tearing open a scar. But if that gives someone else a little bit of hope, it’s worth it.”

One Door Closes…

Toward the end of our conversation, Harley addressed the elephant in the room: the lingering fractures between him and his founding Cro-Mags bandmates. He didn’t name names, but his tone made the dynamic clear—resentment, revisionism, and what he sees as a refusal to move forward. “This is important,” he said, leaning forward. “That window of opportunity is closed. I left the door open for a long time, but they’d rather bitch about the past than build on the work we did. That’s not how I live.”

It’s not just personal. There were real, lasting consequences. Despite multiple attempts to rally the original lineup to take advantage of the 35-year copyright reversion clause, Harley says no one would come to the table. A scheduled call with one bandmate never happened. The label—who provided its own counsel to the then-18-year-old band—refused to produce a contract and reportedly told them to sue if they wanted to move forward. With the window now closed, the rights to Age of Quarrel are lost forever. “We got fucked,” Harley says plainly. “And I tried. Even after Webster Hall. Even after everything.”

Re-Wiring the Chaos

That loss sparked something new.

While working on Wired for Chaos, Harley ran into a familiar problem: how to use Age of Quarrel songs in the soundtrack when the rights weren’t his. The initial plan was to re-record a few tracks as instrumental covers. But as sessions with producer Arthur Rizk progressed, the idea snowballed. “I said ‘fuck it,’” Harley tells me. “I’m recording the whole thing over.”

And so he did. With the 40th anniversary of Age of Quarrel approaching in 2026, Harley re-recorded the entire album—not out of nostalgia, but reclamation. The songs will be registered to their original writers, including longtime vocalist Eric J. Cassanova, who is finally receiving proper credit and royalties through BMI /ASCAP. “I didn’t want the only version of that record that fans could hear to be the one that lines the label’s pockets,” Harley says. “This is my way of ending the quarrel once and for all.”

That act of reclamation—musical, emotional, legal—isn’t just a footnote to the film. It’s an epilogue. A final cathartic gesture from a man who’s spent his life turning damage into something defiant. Harley Flanagan, wired for chaos, is no longer playing for survival. He’s playing to own the legacy that was always his.

What Comes Next

A North American limited digital screening will begin in August, international theatricals beginning in England and Ireland are slated for October, followed by an international digital screening and then the DVD release of Wired for Chaos drops November 11. Streaming and further distribution will roll out over the next year.

Harley’s also back in the studio, working on new Cro-Mags material—though he’s not trying to recapture anything. “I’m not writing for nostalgia,” he says. “I’m writing because the angers still there, aimed differently; but it’s always about being real.”

Realness, for Harley, isn’t a performance. It’s a practice. One that requires honesty, humility, and daily, deliberate effort. “I’m not fixed,” he says. “But I’m better. I can see the truck coming now. Sometimes I can step out of the way. That’s progress.”

And if there’s one message Harley hopes people take from the film, the Q&As, or even just a passing moment with him, it’s this: “You’re not alone. And you don’t have to stay broken forever.” Then, “You just have to stay alive long enough to see what’s on the other side.”

The post Interview: Cro-Mags’ Harley Flanagan: Wired for Chaos, Built for Survival appeared first on Decibel Magazine.