“I’m in a bit of a moth phase,” a park ranger friend of mine mentioned as I scrolled through his latest iNaturalist observations. I tried to cloak my inner voices that were equally impressed by his depth of knowledge and perplexed as to why one would ever be in a moth phase. Little did I know that he had just given me a glimpse into my future.

Like birding, but with moths, mothing is not the most popular North American pastime. More common in the United Kingdom, mothing involves setting up a food or light source and seeing what comes out of the surrounding trees, grass and leaf litter at night. Depending on the time of year, you may attract some beetles, caddisflies and mayflies as well, but, by and large, what you will find waiting for you are moths.

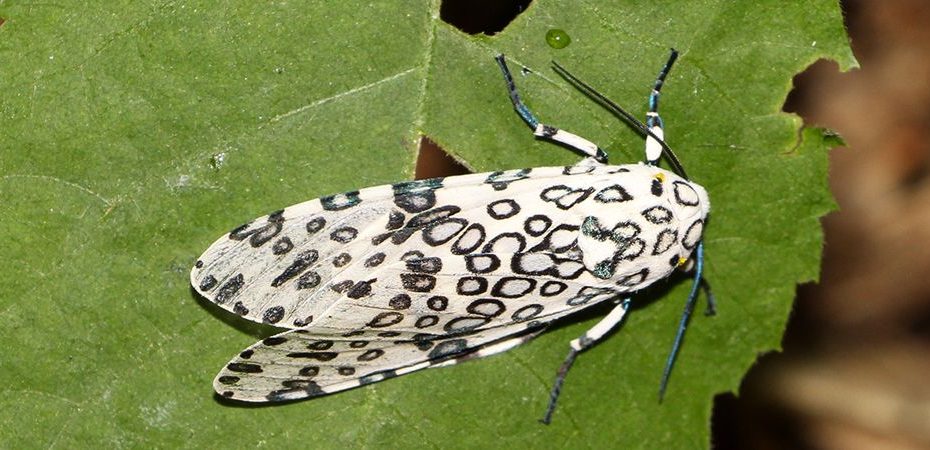

Giant leopard moth, Gananoque Lake Nature Reserve © Jakob Mueller

Why might one want to do this, you ask? For many of the same reasons people have been searching out the birds around us in ever greater numbers each year. Moths are colourful, diverse and fascinating when we take the time to observe them rather than simply swatting them away from our faces.

I didn’t always like moths. In fact, I was terrified of insects as a child. Thankfully, my love of nature managed to cure me of that phobia, for the most part. During the pandemic, I had become captivated by the iNaturalist app that allows you to identify any species by simply taking its photo, and I came up with a project to help pass the time of identifying all of the living things in my yard in Ottawa. I was already fascinated by birds and mammals, and I was eager to increase my knowledge of the plants, fungi and insects that I knew little about. Five years later, I was surprised to learn that a third of the living species around me are moths.

Io moth, Gananoque Lake Nature Reserve © Alice Dabrowski

Whereas there are around 11,000 species of birds in the world, there are over 160,000 species of moths identified worldwide, with likely many more still undiscovered. And that doesn’t even count butterflies, which are genetically just a type of day-flying moth. However, while butterflies tend to symbolize metamorphosis and hope in many cultures, moths tend to be more associated with death and the afterlife, likely due to being largely nocturnal. This is a shame, as moths have much in common with their butterfly cousins.

Like butterflies, moths transform from larval caterpillars into flying adults. Many have brightly coloured and patterned wings that act as camouflage, warning or attraction. Some butterfly and moth species even lack mouths as adults, as they are solely focused on reproduction without needing to eat. Bird lovers should appreciate moths too, as caterpillars are the primary food source for many bird species, turning the tree outside my office window into a huge bird feeder each spring. Once you overcome the fact that they come out at night, moths provide a unique and valuable entry into the natural world.

Thankfully, the barriers for entry into mothing are low. There are generally two means by which moth-ers attract moths: sugar and light. Like butterflies, many moths feed on sugary, energy-rich food sources such as flower nectar. Sugaring trees is one method to attract nearby moths to a convenient place where you can view them. Various recipes are used combining molasses, rotting fruit, dark ale, and sugar. The trick is to create a concoction thick enough to spread on a tree trunk at eye level without it all running off. Once applied, simply return to the spot after dark with a flashlight and see what has stopped by to taste your creation.

Moth light sheet © Adam Fritz

As with many nocturnal insects, moths are also attracted to artificial lights, especially in the ultraviolet (UV) spectrum. The easiest way to start your new mothing hobby is to hang out on your front porch at night. Unfortunately, this is also when moths are most active, so you will likely see more moths flying around your head than sitting patiently for you to take their picture.

The next level up is to purchase a UV light (like the black lights that make the lint on your clothes glow white) and shine it on a white sheet at night to see what you can attract. This will provide a larger viewing area with a clear contrast against the white sheet. If you can invest a little in your new hobby, you can also make a light trap (catch and release only) by taking a plastic container with a lid, gluing a large funnel into a hole in the lid, and placing a light source on top of the funnel. Adding a few egg cartons in the container will provide places for the moths to rest, and you can then remove them to make observations the next morning. Just be sure to empty the container early before it heats up in the sun.

Moth Light Trap © Adam Fritz

The biggest advantage of the light trap is that you can observe the moths you catch the following morning when they are at rest. When used properly, light traps are designed for short-term, catch-and-release observation and do not harm moths; they simply provide a dark, sheltered place for insects to rest until they are released.

While moths are prone to flying away at night, during the day they will sit still, so you can observe them, take their photos and even hold them in your hand if you want. Just avoid touching their wings, as they are covered in delicate scales that will come off if disturbed. A macro lens on your phone or camera can also be very useful to get to see the intricate details of their patterns up close. Once you have finished your observations, simply empty the container in the grass, and the moths will fly off to find shelter.

Will mothing become as popular as birding, or will it remain a fringe hobby for insect enthusiasts and extreme nature lovers? Only time will tell. If you like colourful patterns, finding hidden beauty or simply keeping a list of new discoveries, though, mothing may be the right pastime for you.

Resources

The post Ontario’s Hidden Nightlife: The Fascinating World of Mothing appeared first on Ontario Nature.